“Major, there’s nothing about the 27! … You must include something about the 27!” These were comments from the one-time editor of the pan-African journal Africa World Review Napoleon Abdulai on reviewing Ondoga ori Amaza’s manuscript, that would later be posthumously published under the title, Museveni’s Long March: From Guerilla to Statesman. The “27” that Napoleon Abdulai was referring to are the NRA’s 27-armed men that attacked Kabamba barracks on 1 February 1981, effectively kicking off a five-year guerilla war that would overthrow Milton Obote’s second administration.

The late Ondoga’s is one of the foremost accounts of the NRA Bush War campaign, thanks to its semi-detached scholarly approach to the campaign, nuance many follow-up tales by NRA veterans seem to lack, perhaps due to the proximity of the actors to the action and the passage of time that has seen a hollowing of the NRA/M. As such, accounts like Ondoga’s reveal the innocence of the revolution and to a new reader give a snapshot of the first NRA decade in power.

Revisiting the Bush War

Yet even Ondoga ori Amaza—a medical technologist who joined the NRA ranks in 1982, took classes in political economy and had risen to one of the NRA’s leading ideologues alongside the late Noble Mayombo and Shaban Bantariza—could not escape the intrigues of the NRA, as we now learn from the memoirs of Mzee Matthew Rukikaire, at whose house in Makindye, a Kampala suburb, the 27 young men stayed and plans for the Kabamba attack were hatched.

Rukikaire and Amama Mbabazi would constitute the NRA’s External Wing which also included leading Ugandan exiles Sam Njuba, Ruhakana Rugunda, Sam Katabarwa, Zak Kaheru, among others. The external committee of the NRA was tasked with fundraising abroad to support the war effort in Uganda. It is a task for which the committee members have received a lot of flak, accused by NRA fighters of living the high life while their peers had to make do with barely anything to eat in the bushes of Luweero.

Pecos Kutesa, for example, describing his trip to Nairobi and the meeting with Mbabazi and Katabarwa writes,

“We the bush people, were mesmerized by the grandeur of the streets. The well-paved roads, the sleek cars, the neon lights, the smart sidewalks, the flower garden, but mostly how our people, Katabarwa and Mbabazi, fitted into the picture. I started wondering if we were in the same war as the External Committee people.”

Ondoga re-echoes the same frustration.

“Then, of course, there was always the hope that the movement’s external wing, supposed to be mobilizing support abroad, would send in arms sooner or later. As it turned out, however, the people of the external wing proved absolutely useless in as far as acquisition of arms for the struggle was concerned. The only times when arms came from outside were when Museveni himself brought them in…”

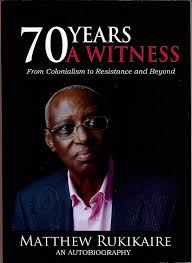

In the memoirs, 70 Years a Witness, Mzee Rukikaire disputes this account of events and told me in a February interview that he suspects such was a well calculated attempt by the leadership in the bush (supposedly Museveni) to undermine the committee’s role in the struggle. “Instead of trying to help explain the nature of our work, especially Mbabazi and Katabarwa’s work, the bush war leadership either turned a blind eye or joined the voices of criticism of the group,” he writes.

The extent of “sacrifice” by external committee members came to the fore in the fall out between Mbabazi and Museveni in 2014. According to the Observer, in one of the NRM Central Executive Committee meetings convened by Museveni to decide Mbabazi’s fate as the party’s secretary general, accusations of leading a privileged life while in exile were leveled against the former prime minister. “You people were busy in Nairobi eating sausages and stealing our money. Should we have sympathy for you? Can I remove my trouser and show you the bullet wounds?” a charged Matayo Kyaligonza, former commander of the NRA’s urban terror outfit and now NRM Vice Chairman for Western Uganda, was reported as saying.

Rukikaire, who is also Mbabazi’s in-law—his son Philip marries the former prime minister’s daughter, Nina—dedicates an entire chapter in the book to clarifying some of these allegations.

“As Amama Mbabazi pointed out in 2006 at Museveni’s country home in Rwakitura, it was not the role of civilians to search for arms. There was a taskforce of Amama Mbabazi and Sam Katabarwa assigned to that responsibility… There was also the fact that Museveni himself had come and stayed for long spells of time and not succeeded in procuring any arms. I know that he had been knocking at Nyerere’s door, as Mbabazi was always doing, to no avail,” he writes.

Earlier in the book Rukikaire also mentions how he offered two guns—an AK47 to Museveni and a pistol to Andrew Lutaya, who was the driver of the truck carrying the NRA fighters that attacked Kabamba. It is the first time we are learning about the two weapons donated to the war cause as well as a consignment of arms from Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya that were delivered to Bujumbura, Burundi and transported to to the NRA in Uganda using fuel trucks owned by Rukikaire’s friend Girigori Karuletwa. “I have rarely seen or handled such a smooth operation,” recalls Mzee Rukikaire.

Perhaps the book’s greatest strength is that it offers a new look into how the NRA bush war was procured, from the vantage point of a non-combatant, Matthew Rukikaire, who knew Museveni first as a student—he was his student-teacher at Ntare School; to a General Service Unit (GSU) officer in Obote’s office; and as an exile in Arusha, all before the start of the bush war in 1981. He observes Museveni as a “strong-willed young man, seemingly lost in his own world,” a world of Marxism and a fascination with Fanon’s ideas on violence was what Rukikaire found rather alarming about Museveni in 1971.

Describing his second meeting with Museveni seven years later, arranged by Museveni’s in-law Sam Kutesa, Rukikaire finds the guerrilla leader’s ideas to have evolved from radical to more mainstream and this informs his decision to support the Museveni’s FRONASA outfit, a precursor to the NRA.

“I made it clear at the end of the meeting that I would give him my support and he appreciated the gesture. Kutesa remained doubtful and wasn’t ready to give similar assurances. […] and I wonder whether, even as early as then, [Kutesa] did not habour ambitions of becoming president one day and whether he didn’t regard Museveni as a possible future rival in that regard.”

In this brief but revealing account one is confronted by Museveni’s evolution as a formidable politician—always willing to compromise and one who is not held prisoner to his ideals. It is perhaps this character that many of his peers—Kategaya, Mbabazi, Kizza Besigye, Tinyefuza, would later misdiagnose as “betrayal” in their fall-outs with him. On the fall-out between Museveni, to which the author dedicates the final chapter of the book, not even Rukikaire’s closeness to the two men bears the reader any answers. He however acknowledges that Mbabazi’s departure from the ruling NRM party is a “loss of immense proportions” and reserves the book’s end to the discussion on transition within the NRM and the national presidency, a debate he thinks is quite timely and ought to be handled with the seriousness it deserves.

The book’s opening three chapters, except for the keen reader interested in the author’s biography, are not as captivating and serve only the purpose of prepping one to understand the relationships between the author and various other actors who would go on to play important roles in Uganda’s liberation story twenty years later. A token of gratitude, however, for the author’s narration style and keen attention to dates, events and anecdotes in his youth that would have a significant bearing on Uganda’s history as a whole.

Postscript

Following the launch of Mzee Rukikaire’s memoirs 70 Years a Witness at the tail end of 2019, I had chance to host the veteran businessman and politician at the LéO Africa Institute in February 2020. In the interactive session with fellows of the Institute, he re-echoed the need for the young generation to prepare for the imminent transition and the need for them to learn from the mistakes of past leaders that had brought the country to the precipice in the 1980s. He also acknowledged the immense economic turn around the country has witnessed under the NRM, but was worried this prosperity and stability was under threat from unchecked public sector corruption and a growing intolerance for divergent views by the ruling party.

Matthew Rukikaire’s 70 Years a Witness offers a comprehensive account of contemporary Uganda’s history from the tail end of colonialism, to the promising dawn of independence, the desecration of its institutions and disintegration of the Ugandan state under Amin, and the Resistance war that heralded into power Museveni’s NRM government. Few actors have been privileged to be so close to the NRM establishment, from its formation, through its various transformations, disagreed with Museveni and yet retained a distance that accords them the ability to scrutinize the movement without being passed off as “disgruntled”. Mzee Rukikaire manages to accomplish that in a life one can only sum up as well lived!