The Politics of Common Sense is a collection of articles the author, David F.K. Mpanga, submitted to a newspaper column in the Daily Monitor, one of the national dailies in Uganda. The articles were written between 2006 and 2016 and are a good flashback to the local and global events of that time viewed through global, continental, regional, national, and sometimes tribal lenses. For flow, the book is organized in chapters that group together articles on key topics: analogies and practical philosophies, geopolitics, constitutionalism in Uganda, economy and corporate governance, corruption, education and health, history, politics (obviously) and corporate governance, good manners and some gems from the archives.

In the period these articles were written, I had already decided that daily consumption of news was depressing. Social media was picking up as an alternative for getting the important headlines so I was barely reading newspapers. I was also heavily jaded by the state of politics and identified as anti-politics. I wasn’t the target demographic. Reading this book was therefore my first encounter with Mpanga’s writing. If you are not familiar with the name, David F.K. Mpanga is one of the most prominent lawyers in Uganda, and the Minister for Special Duties in the Buganda Kingdom, among other things. For nonfiction books, the author’s profile is what usually drives me to pick interest in reading, and Mpanga’s had me curious about what he had to say.

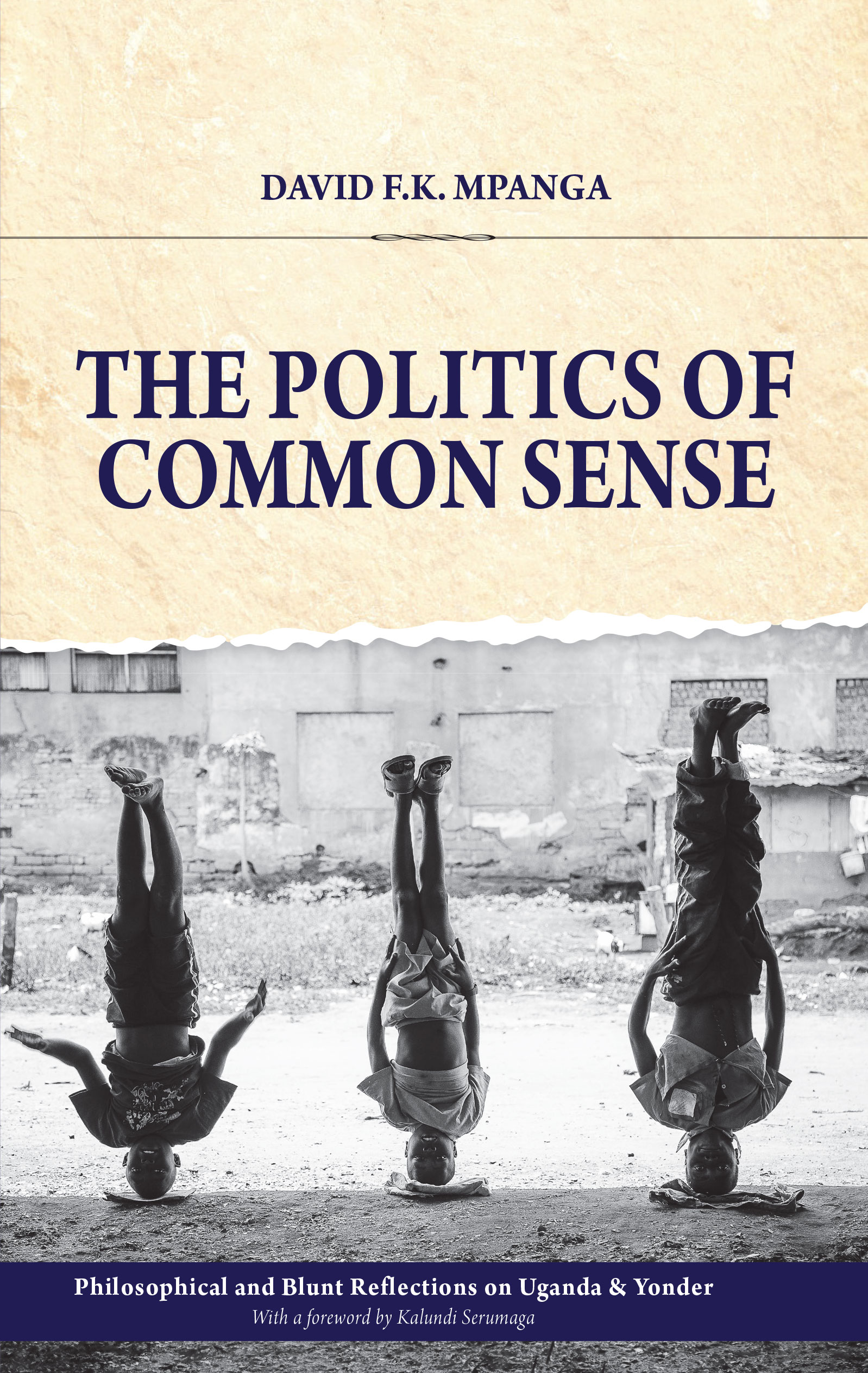

I like the title. The Politics of Common Sense. It’s catchy and makes you think about the combination of the two keywords. Politics and Common Sense. The first thing that came to mind was water and oil, not exactly famous for mixing. I also like the book cover and choice of image. Those three boys doing flawless headstands juxtapositioned with the title make it amusingly depressing (forgive me if this word appears frequently. It’s one I generally associate with politics). In one of the articles, Mpanga explains why he chose that title for his newspaper column: Common sense means sound practical judgment. The title is therefore more or less a call for this in local and international affairs and a commentary on the absence of it in the different issues he delves into in the articles, hence the political aspect of it.

Personally, I have issues with the word common sense. As a mischievous child, I was occasionally told how I was lacking in common sense by my parents. This is how I became familiar with the famous oxymoron about how common sense isn’t common. And I have since embraced that as I continue to discover how layered and complicated humanity and our decision-making processes are, more so to those in leadership positions. Constant sound practical judgment is something left for the idealists and this is something that is reinforced as you go through the themes and topics explored in the book. This doesn’t negate the need to hope and aim for the ideal and that is the attitude the writing takes.

Being the lawyer he is, which makes him very careful with words and their meaning, Mpanga makes compelling points with his persuasive argumentation. From oil discovery and exploration to elections in Uganda and beyond; to the Arab spring; to Buganda and Uganda’s history; to the 2008 economic crisis, to Brexit…there is no shortage of sensible analysis and observations. There are some practical suggestions on how things could have been done differently in some of the scenarios he takes apart but for the most part, the nature of the writing is meant to leave you reflecting. This sounds like a good thing but it became my main beef with the book, anha, what next after reflection?

Mpanga sounds like the kind of person you want in high up positions running things. And it seems I was not the only one thinking this because, in one of the articles, he mentions readers asking him what he is doing about all the loopholes he points out in the systems he so accurately observes. His response was the column and the role it plays in examining the issues from a different perspective to trigger thought and action among the readers. That’s all well and good but I left with the feeling that like most people that have succeeded in the private sector, the mess that is political office, where actual policy and change are made, is not that alluring. I grudgingly respect that.

The problem is that the words of the critic often go ignored by those whose actions they address. This is evident in the reasons Mpanga stopped writing the column, he was starting to repeat himself. The issues he had examined in the news cycle kept on happening and it was brought to his attention by his wife that his arguments were being repeated. As an example, he copy-and-pasted an article word for word about the Ugandan education system a year after it came out and, lo and behold, everything was still valid. The real kicker is that his late father, Fredrick Mpanga, a lawyer turned journalist in exile had made similar arguments in his writing 50 years earlier. Depressing I tell you.

PS: The side theme on discovering his father, who passed on when David was only six due to the kind of circumstances that could have been avoided with common sense, and carrying on his legacy was one of the most engrossing for me.

In the absence of solutions to the issues addressed, why then would one read the book if you are already jaded, as most of the target readership is about all things political?

It is the storytelling for me.

Mpanga is a gifted storyteller in the ways of the land. Considering his involvement in the Buganda kingdom administration, I would have been disappointed if it had been any other way. And while we are on that topic, my other tiff with the book is I, considering Mpanga’s proximity to the top, expected more Buganda insights on how the Kingdom is pivoting in these changing times.

The true credit for Mpanga’s storytelling gift, though, is his grandmother. In one of the articles, he talks about how he and his siblings while growing up spent many hours listening to her weave Luganda stories and folklore in that African oral storytelling tradition that relies on proverbs and other tools to say things without saying them. But, as Kalundi Serumaga pointed out in his foreword to the book, this storytelling/arguing style doesn’t easily translate to English and yet, Mpanga manages to pull it off. The book is also littered with quotes from other books, thought leaders from different times and parts of the world, personal anecdotes from his life and surroundings at the time of writing – all of which are well weaved together to keep you glued to the pages.

The Politics of Common Sense is a deep dive into our country’s and region’s past, how that affects the present, and how our actions in the present will affect the future. Despite my jadedness, there is a recurring call to action: to do better and be more proactive if we are to protect our future from the potential chaos it might face with the current developments in global politics and economics.

In the introduction, he states that the goal of the column and this book was to provoke rational analysis and constructive thoughts that would lead to positive and sustained engagement by citizens in the political world around them and, speaking for myself, he succeeded at this goal. I am a renewed believer in the pursuit of common sense in politics.

Roland Niwagaba is the founder of Muwado.com and a 2018 Fellow of the LéO Africa Institute.