In his book ‘Artist the Ruler’, Okot p Bitek, suggests that within traditional Luo society, the artist was something of storyteller and a seer. And since the vocation was the preserve of a few, artists wielded considerable influence in the Luo community. As such, they could speak their to those in authority without fear of repercussions as would likely be the case for other subjects.

Moses Serubiri, an arts curator, argues that art has had its place in society long before politics became the norm, “However, I understand that these earlier processes of the 15th and 16th centuries were present and part of creative and artistic pursuits. Here, I mean to say that before the modern period of political society, art and culture seemed to take a much more elaborate role.”

Artists speak through their works. These works are an expression of their feeling but most importantly, they tell the stories of the time and how the lay man understands it. Art is a language that is spoken by a few yet understood by many. One does not need to have gone to school to interpret the stories.

Alex Kwizera is an artist and art entrepreneur who runs Kwizera Studio, he tells me art is the bridge that connects the eye to the other senses and a universal language understood by all.

Yet with all this, often times, artists are not always welcome in society.

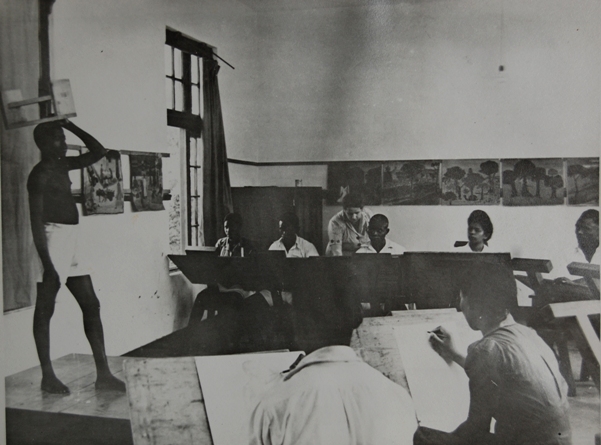

At Makerere University, Uganda’s oldest institution of higher learning, the Department of Industrial Art and Design (DIAD) was only established in 1995, much as the teaching of the subject had been around since the 1940s.

Studying the Arts in general is still largely frowned upon. President Yoweri Museveni, while commissioning a modern laboratory at Ndejje University in 2014 said graduates from such departments (the arts) can hardly solve anything to steer national development.

Add to this the high sense of expression that many artists have about them; to be an artist in Uganda is to be what in Runyankore they call endeme. Maria Natia Kakonge, an artist, sculptor and academic at Makerere University, in an interview with the African Secrets Magazine in 2017 said “The idea that sparked my interest and dedication to art was that I’d have the power that I’d make any shape… then the clay became my first love and that’s how I started attempting sculptures.”

In the Beginning

Artists have always taken to their brushes and canvases to express themselves. Serubiri says, “I know that musicians in the palace of Buganda, were given precedence over others to provide critical remarks, as well as being seen as intellectuals who could challenge the political discourse of Buganda society.”

According to Serubiri, when the colonialists came to Uganda, they did not consider art as a commodity for the locals to consume. “The argument from a colonial administrative perspective was always that Ugandans did not need to make art before they built roads, and schools and expanded their economies.”

Serubiri recalls an argument made in the 1950s, “’Modern Ugandan art was derided by Makerere University students commenting in the campus newspaper in the 1950s, as a mere copy of Picasso.”

As a result, he suggests,”There is a lack of art appreciation in Uganda, Kenya, and elsewhere, regarding local Ugandan art history.”

It took the efforts of Margaret Trowell, a British artist, and her husband Dr. Hugh Trowell, then serving as a doctor in the Colonial Medical Service, to establish an indigenized art curriculum at Makerere University.

The now famous Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts (MTSIFA) at Makerere has its humble origin on the veranda of the Trowell’s residence in Mulago in 1937.

George Kyeyune, an Associate Professor at the Department of Industrial Arts and Applied Design (DIAAD) at Makerere University, writes in ‘Arts in Uganda in the 20th Century’ saying, “In 1962; the intellectual climate resounded with debates about indigenisation. Against this ideological backdrop of cultural renewal and discovery, some artists returned to a version of Trowell’s philosophy of Africanising of art education.”

It was the change in the political atmosphere in post-colonial Uganda in the 1960s and 70s that changed the role of artists, Kyeyune continues, “The promising political climate of the 1960s was soon replaced by repression and the civil war between 1971 and 1985.”

These conditions led to three important developments according to Kyeyune. “Firstly, artists continued to create overtly political images, which expressed disgust for leaders. Secondly, new media like batik, better adapted to economies of scarcity, proliferated.” And finally, “With shortage of imported materials and tools, artists investigated local materials under the influence of Francis Nnaggenda.”

For Kyeyune, ironically, an art that utilised local themes and resources “arose from the adversity of the 1970s, rather than the favourable climate of the 1960s.”

To date, the culture of buying paintings and other works of art stays distanced from many a Ugandan. Craft villages are mainly visited by tourists in search of souvenirs. There is a general detachment among a number of Ugandans about art in general. Titus Segawa, a dentist, tells me he only goes to the craft village when he needs to buy a gift for someone.

There is also a push-back against popular art pieces such as one portraying ‘pregnant black woman’ carrying a child on her back and balancing a stash of wood on her head that have been reproduced over time for promoting negative stereotypes about the African woman and her lifestyle as a whole.

The African woman lifestyle is diverse and deserves to be portrayed in that light, however, “The artist also has to consider making an art piece that sells. If the above art piece sells, it only makes sense that it will be reproduced again,” says artist Micheal Lutaya of Bafrika Creations Gallery in Entebbe.

Art is a serious, full-time business

Most artists do art as a full-time business. As such, at the confluence of market demands and the need for steady means of sustenance, often lies an uncomfortable trade-off.

A number of artists in Uganda have to rely on the craft village to have their stock sold. Others make use of exhibitions to make bigger sales.

Today, unlike before, artists work more in groups than isolation. With better technology, artists are now selling their works online. They have created websites where they sell their works. Social media platforms like instagram have been a change in force. Neema Iyer, an artist and designer sells her art work on her website (www.neemaiyer.com). She also uses her instagram account (neemascribbles) to share her work.

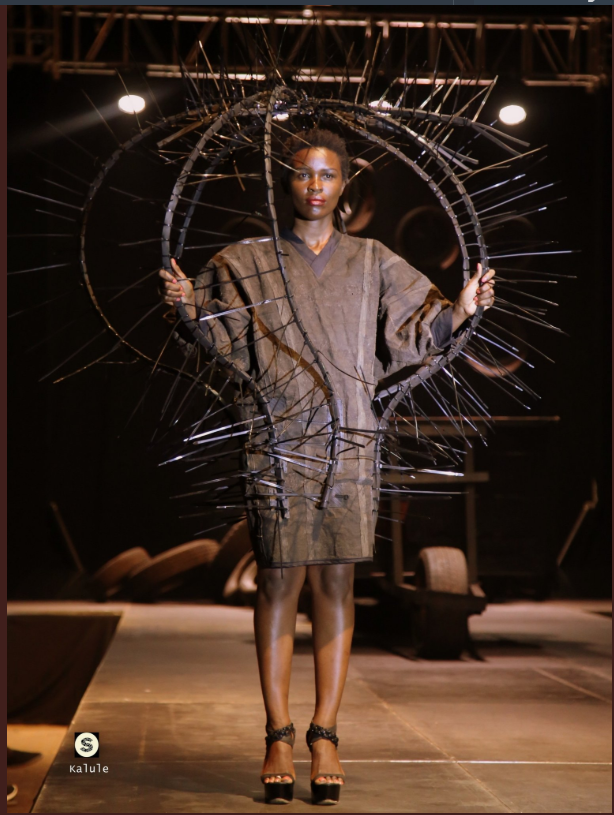

Different artists have also taken to exploring unique techniques to better their art. Xenson Senkaaba’s recent exhibition, Gun Flower Mask showcased a number of products he made from old tyres.

At the exhibition, Xenson showcased the role of art in conserving the environment. He made bags, sandals and jackets from discarded tyres. Simon Kaheru one of the attendees of the exhibition quotes Xenson in a tweet saying, We all wear masks. Flowers remind us nature will continue in spite of our actions.

Hillary Mugizi alias Ezi has for the last decade sharpened his skill of vector art, a distinction that has set him apart. Hillary uses a technique of using the art of symmetry, line and angles to make his painting.

His work has attracted attention from international artistes like Konshens and Neyo who have described his work as distinguished. Hillary has made his work known by sharing it on his Instagram, Fcaebook and Twitter social media platforms under his moniker Ezi Wear. “To see my work being accessed by the people I will never meet in life is something that humbles me.”

Yet, with all the innovations in the sphere of art, artists have kept their art true to the connections of the communities in which they stay, identifying with the wrongs, celebrating what is right, and giving hope to the broken.

With more spaces being developed, artists have commanded the attention and respect of society today more than ever before. Hillary tells me, “I was asked to give a talk at Gems Cambridge International School and afterwards I was given a contract to design their vans.”

Micheal Lutaya of Bafrika Creationz Gallery in Entebbe conducts a holiday program that teaches children to paint. “Their parents entrust us with them to teach them painting other than staying at home idle. At the end of the holiday, every child has an art piece that they carry home.”

Beyond painting

Today, art is beyond the stroking of the brush on the screen.

Katoto, an animation cartoon by Richard Musinguzi caught media attention when it premiered on YouTube in 2014.

The character Katoto is an ordinary Kiga man who lives a hilarious life. The creator translates Katoto’s Rukiga into English without missing out on the heavy accent that is characteristic of Rukiga speakers.

The influence of this comic animation caught the attention of the Ugandan YouTube audience and soon advertisers had latched onto the comic to market their products. Katoto’s YouTube series have since then attracted a local bank as well as President Museveni whose 2016 campaign adopted some of Katoto’s skits.

Beyond the stroking of the brushes, art is sustaining lives. It is improving households but most importantly, it is engraving eternal memories in the minds of those who consume it.

Art is therapeutic. It heals people. When they see, they remember, they learn, they renew their hope. Important of it all, art gets humankind to speak the universal language, the one understood by everyone in their own accord.

Like Margaet Trowell argued in her book African Arts and Crafts, “Art was far more important in the education of the child or convert than is argument, because it appeals to our subconscious emotions which lie deeper than our rational mind.”

In that vein, art stubbornly refuses to conform. The politician who jails a cartoonist he deems critical often than not finds himself appealing to another visual artist to produce skits for his election campaign.