Kwezi Tabaro: Good afternoon and welcome to this conversation series.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Good afternoon Mr. Kwezi Tabaro. I am so honored to be here. Thank you for hosting me.

Kwezi Tabaro: I hope you listened to the drums that were played before this conversation started.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I did. I think I created that with my friends in Oakland, New Zealand sometime last year.

Kwezi Tabaro: Please tell us more about them. Are these Ugandan beats?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: [laughs] No. They are not Ugandan and I don’t think they can be. Probably the only Ugandan thing about them is just me. I had friends from New Zealand, one from Ghana, […] one from Kentucky, Nigeria, Botswana, the UK, then I had one from Zimbabwe, and then I had another from the (sic) Congo. So, we just came together and created that; and when you have such diversity, nationalities definitely have to take the backseat and let creativity take its course.

Kwezi Tabaro: So, this is an Afro-fusion of sorts?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: yeah, you can call it (an) afro-fusion; some kind of pan-Africanism being expressed in music: in this case drums.

Kwezi Tabaro: Interesting. Good to have you Mabingo and you know, while I was preparing for this conversation, I landed on notes I had written the very first time I interviewed you on 21 June 2014 [at the Writivism festival]. I don’t know if you remember our conversation.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I do remember our conversation.

Kwezi Tabaro: The topic of the conversation then was the Substance Of 21st Century Pan-African Intellectualism, Art and Expression, which is not so far off from what we are going to discuss in our chat today.

Now, briefly, tell me about this dream to be a dance scholar that started with you trying out at being a catholic priest, and then later a lawyer before you eventually landed on dance in 2002.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I think I can say that I am just a child of fate. So originally, as you have briefly outlined, my intention wasn’t to end up where I am now. It was completely another universe that I was envisaging to be in and that didn’t happen. So, I won’t go back into that history, I will just take you to 2002 when I was admitted for a degree in dance at the university.

How did this come about? So, that year, we were having a traditional application, the JAB forms, for A-Level. I applied for Law, Mass Communication, and all that, and then we had courses that were introduced, I think, around February or March of that year. When I heard of these new courses; Human Resource was one of them, International Business, Entrepreneurship, and then a Bachelor of Arts degree in Dance.

And so, I applied and put that [Bachelor of Arts degree in Dance] course as well because I just wanted to fill the positions, they were six, and it was number six. That is the course I was given on government sponsorship. So that’s how I start crawling back into this world of dance and music and it wasn’t easy to transit. I had to re-orient my thinking to accept that I was going to be a performing artist. But I had systems to manage that as an individual and I think I made the right decision: so, here I am.

Kwezi Tabaro: You credit a lot of your interests and skills in dance to what you called “village life and experience” that has always been the sole genesis of your artistic creativity and vision. Did your upbringing in Mpigi, in rural Uganda, shape in any way your interests in dance?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Uhmm, I wouldn’t say it shaped my interest in dance then because I didn’t even know that someone would pursue or even develop a career in dance. So, it was something we did as children; you would make music, make instruments, play music, dance, play games: it’s part of life. Its life.

It is so transient; it exists and then it goes and you go on with your dreams. That kind of experience I had in that environment disappeared when I went to a boarding school, middle school, but it was lying deep somewhere, and I rediscovered it when I started studying music, dance and drama at Makerere University—and then everything started making sense.

It was more, you can say, retrospective, in that sense. So, I started making that journey to my past and trying to make sense out of that kind of childhood and upbringing; the creativity. I started rationalizing that experience in retrospect and I discovered that it was rich, it was authentic, it was meaningful, and above all, it was meant to shape humanity and shape someone to be a better citizen of this world.

I still go back to that past and consider it the foundation and launchpad for my writings or the models that I have developed to create and teach music and dance, or the theories I am trying to develop and write about in this field of music and dance.

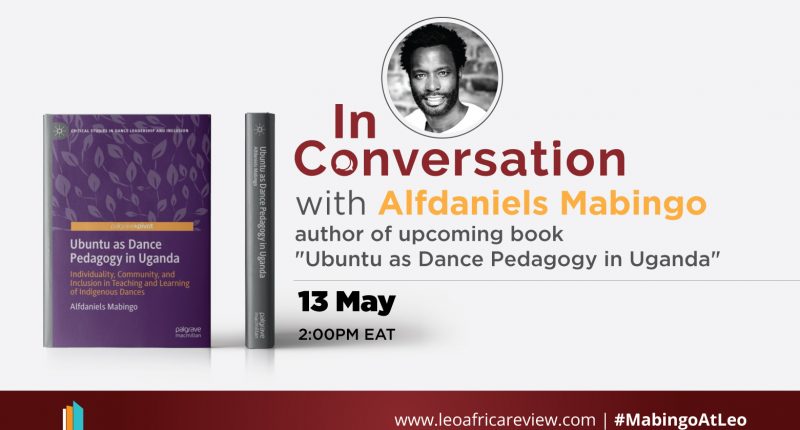

Kwezi Tabaro: You know, it’s been an 18-year journey trying to study and understand music and the culmination of which is an upcoming book, “Ubuntu as Dance Pedagogy in Uganda”. I know the title is coming out later this year but I wanted to take you back to something you wrote in 2012 in an opinion piece for The Daily Monitor.

You said, and I quote, “People have always enjoyed the freedom that arts provide for expression. Originally, communities in Africa used to create, recreate, perform, share, and appreciate the arts as a community. It is this unifying communal philosophy that gave birth to the current ethnic music and traditional dances that we enjoy today.”

Now, the question from that is: Is this where you derive this concept of Ubuntu, which is, I believe, a central idea in your teaching of dance both in Uganda and all over the world where you have had the opportunity to teach pedagogy of dance; but also, is this the reason why it is such an underlying theme in your book?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I think it is more of an expression that tries to touch that theme of Ubuntu. But at the time I wrote that article, I’ve written many for The Daily Monitor in that respect over the years, I hadn’t yet investigated further this idea of Ubuntu as a central theme and as an underlying philosophy or world view that informs the way we think, the way we know, the way we become and the also the way we identify.

But, my thinking along those lines started forming around that time when I started to investigate more the thinking behind how we create, how we perform and how we share art. It’s something that has been developing for quite some time and it has taken quite a great deal of investigation for me to get to a point where I was really confident and comfortable to expand that and construct it into this wonderful book that I have written and will be coming out in the second half of this year.

Kwezi Tabaro: Maybe, for our audience, you could expound on this concept of Ubuntu and how it relates to the teaching of dances.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I think the person who really compressed it and simplified it best was the late African philosopher John Mbiti. He wrote a book on African religion and philosophy. Mbiti summarized Ubuntu as an experience, a feeling, a practice, a way of thinking that is represented by the expression “I am because we are and because we are, therefore I am” and so within our tradition and within our practice and our thinking, and by “we” I mean generally communities across Africa, there is that idea of caring for one another.

So, our form of individualism is a kind of individualism that recognizes the presence and the importance and relevance of other individuals within a community and also within ourselves as human beings. That is what connects us, that is what makes someone say “Okay, I will contribute to someone’s introduction [ceremony]” even when they don’t know them. We still have that spirit which, if you travel to the western world, you realize they have quite a huge deficit. So, I see that in the way knowledge of dances is shared, I see it in performances of dances especially in communities that haven’t been touched by the neo-liberal economic mindset. My book centers on those communities that are standing a bit outside that paradigm of neo-liberalism and that is where I derive my thinking and the configuration and construction that I make around how that philosophy of Ubuntu intercedes with how those communities teach indigenous dances.

Kwezi Tabaro: I remember one of our conversations about traditional dances in Uganda; I am only familiar with Uganda, so maybe you can enlighten me if the case is the same elsewhere in Africa, that our traditional dances tend to involve more than one individual, at least four or five individuals. It’s an ensemble of dancers: there is a drummer, there is a dancer and dancing itself is storytelling, and in a way, the medium through which traditional values and information are shared. Is this how it relates to communalism and Ubuntu?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Yes. That’s what I hint on. There is that kind of plurality that derives from individuality. If you analyze it well, and take time and try and track how that system is organized, exercised, and celebrated, you realize that there is a strong focus on individual innovation. But then, that individual innovation then exists within that space of other individuals.

So, it’s those different individualities that congregate and then they create something that is taken as a communal good and also extends into a communal experience. I think that our traditional indigenous dances are unique in that sense but my travel has taught me that it actually cuts across quite a number of native communities. I work a lot in the Caribbean: in Jamaica, in Barbados, in the Bahamas and you find the same kind of spirit and the same kind of practice. I work a lot with communities from the Pacific: Tonga, Samoa, Niue, Cook Islands and a number of other nations in the pacific and you really find that kind of spirit and that kind of thinking is still central to how they approach processes of creating.

And so, it’s something that I think is unique to communities that are not considered western in that meaning of capitalistic societies. And I am still investigating to find out why that pattern still exists.

Kwezi Tabaro: And I know your teaching of dance has taken you to countries like Jamaica, where we see a mixture of both native populations but also recent immigrants, and the mix, one would assume, would produce something that’s different from somewhere in Africa or elsewhere in the Caribbean where you have smaller, more native societies.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Yes and no. Yes, in the sense that if you look at just the form as art, and I am speaking about Jamaica specifically where I have been doing some extensive work in the education and research, so for example look at dancehall. Dancehall is a form that emerged in the 70s but is really unique from Hip-hop which also emerged around the same period of time and it’s just next door in the United States of America.

So, you realize that Dancehall is just different from Hip-hop, and in that sense, they create something that is really unique to Jamaica. But also, the spirit; what I discovered is that the spirit and their desire is purely African. Now, we can go into defining what African means but I think by and large, from my experience I discovered that Jamaica is a country that is really proud to be African. So, the spirit in that sense or you can call it the software, still leans more towards Africa; they look back: Like the Sankofa [a mythical African bird that moves forward while its head is turned backward toward a golden egg on its back], they always look back. When they create, they always look back at the environment and where they are and their history—being a country that was created out of the middle passage, and they create something that responds to that kind of heritage. So, I found that blend to be rich and also interesting in so many ways.

Kwezi Tabaro: Hold on to that thought. I want you to step back and answer the question that from one of the participants, Lisa Wilson, who is asking: How does one manifest Ubuntu meaningfully in the dance class with students from diverse cultures and dance training that can often carry erratic norms of each other?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I think for me, having taught in Europe, North America, and Australia, and that is what guides my pedagogic philosophy, what I try to tell my students, my collaborators and participants is that one, let’s first create an experience for everybody and so when you approach it from an experiential perspective, then you bring in the idea of inclusion because any person can contribute to an experience.

So, I try to make the experience the overarching central theme and that brings everybody together because everyone has an experience to share. I also try to discourage, as much as possible, this western objectifying notion that a dancer must have this body, a dancer must be this perfect and try to create a space, and I call it a safe space, for different individuals to come and be. I emphasize that and once you open the space for different individuals to come in and be and you also remind them that it is non-judgmental; so bodies are not being judged, then you realize that people experience that freedom and they innovate more, create more, collaborate more, share more and keep on adding those layers that form an experience within that space.

I think and believe that advances come from that perspective and that kind of thinking and if they are to be shared, I think that thinking should be maintained regardless of where that kind of activity is being convened.

But of course, I also recognize that communities have their unique circumstances and they have their unique needs and so I try as much as possible to understand what are the needs, what are the circumstances of this particular community, particular class or even to a very large extent particular individuals who come and partake in the dance activities.

I also emphasize this, and I think the world needs to know; Ubuntu is learned but it is not taught. It is lived. You are born into it. If you are born into a society that doesn’t celebrate it in all facets of life, you can’t teach it. At school you teach it and then at home the children are being told “You are an individual. You have to do better than Jane, your sister, you have to do better than Peter” you know, that kind of competitive environment; if you teach it at school and it doesn’t exist at home, you are wasting your time. So, I tell people that back home in Africa, we are born into it, we live it and then we learn it.

You can’t design a course outline like they did one day in the US; they asked me to go teach Ubuntu and I turned down the invitation and told them I can’t waste my time to teach Ubuntu in New York City where students are on their iPad or their iPhone for 10 hours a day and they don’t to relate to someone who is next to them.

I recognize those constraints when I try to pursue the idea that this can be expanded or disseminated across different global demographics.

Kwezi Tabaro: Thank you. And thank you Lisa for the question. Now, Mabingo, I would like to take you back to the Sankofa philosophy that we had talked about from Ghana: Looking back. In one of your papers you talk about two prominent African thought leaders who have articulated two complementary visions for the development of black people. On one hand, you have Molefi Asante who has advocated for he has called “Afrocentricity” which is a system of thought that considers the African world view as a key driver of human progress and on the other hand you have the late Prof. Ali Mazrui who has suggested that through something he calls “horizontal interpenetration”, black people across geographical locations can exchange ideas and experiences as a way of advancing self-empowerment and actualization in this era of western hegemonic trends like neo-liberalism. How are you as a black scholar of dance using the pedagogies of African dances to advance such visions? Do you subscribe to any at all?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Yeah, I do and I strongly subscribe to quite a number of those theories and the thinkers, and that’s why I really draw on a number of resources that these thinkers have generously shared with us to try and advance the case for dance education. I think that quote came from an article that I wrote about my work in China. To just expound further, I think for me as a scholar, there is a statement that the late Ali Mazrui made that “to be a giant you need to stand on the shoulders of other giants”. So I think that if we are to position our dances and our dance epistemology knowledge competitively and claim space in global scholarship and research, I think we need to figure out how we can engage our own thinkers to make a case for our knowledge to add more value and validity to the knowledge we generate through research or even the kind of teaching and learning methods that we develop as teachers. So, my work draws on a number of scholars: Asante (Molefi), Ali Mazrui is big, Ngugi wa Nthiong’O is big, Valentino Y Mudimbe, that wonderful African philosopher. I also extend it to people like Frantz Fanon, and I also move outside the continent and look at people like the late Edward Said who wrote a wonderful book, “Orientalism”. So, I think we need to engage all these different voices to try and locate our own voice and to try and develop models that draw on those different intellectual heritages to just create something new; something that is really suitable and something that is really relevant to dance studies in Africa.

Kwezi Tabaro: Now, you know in Uganda, or for that matter in many parts of Africa, if someone says that they are a dancer or a dance instructor, the idea is that this is their trade, the way someone is a teacher or a lawyer and that all they do is perform for pay especially abroad and outside our communities. As a result of that, you have had a number of cultural “dance troupes”—some of them include orphanages—that have become popular for going out there, performing and earning a living out of that. But the way you approach dance is a little bit different; yours is music, dance, and drama as a tool in the classroom for teaching. Where do you draw the distinction or is there a distinction to start with?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I don’t think there is any distinction to be very honest with you. Why am I saying this? Our art stands on—if it was the traditional fireplace, Ekyooto, in my Mpigi-Buwama-Mawokota thinking, you have so many stones, amasiga. So, our art stands on quite a number of stones, you can call them strands or pillars: you have performance, choreography, functionality and then you have pedagogy.

All these different pillars work in concert. It’s a concert. So, I cannot go and find out knowledge about how people learn and teach if they don’t do it and when they do it that is performance. I can’t find knowledge about what they do if they don’t create it. And still, I can’t find this relevance of pedagogy if I don’t find out the functionality; why are they doing it? So, I think, to bring back the conversation to your question, performance, pedagogy, choreography, and cultural interpretation of the dances, they all work hand in hand. What I try to do in my research and my scholarship is to introduce pedagogy as a domain of knowledge that is not distinct, a domain of knowledge that works in concert with other domains of knowledge but at the same time has its own unique characteristics.

People have looked at dance from a performance perspective, from a choreographic perspective; we have so many people that have talked about the functional aspects of dance, et cetera. I come in to look at the pedagogic aspect and I think this pedagogic aspect is so central because it speaks to how this knowledge is transmitted from, either, a person to another person, from one context to another.

But I recognize the importance of other aspects and other facets of dance performance because without them, I cannot qualify pedagogy as an underpinning domain of dance practice.

Kwezi Tabaro: You go on to say that total education of a learner needs to stimulate what you define as “multiple intelligences”. Maybe you could expound on that?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: That’s a very good question. So, I will take you back. A challenge we have had with our dances, and you hinted on it, is that if you read the books of history or even if you interviewed people on the streets of Kampala or even Makerere University; if you entered offices of professors and you asked them about dance, they will tell you “It’s something that people just do to feel happy: it’s about merrymaking.” When I did my research for my Ph.D., I went to the university library at Makerere University. That library, especially the Africana section, has a lot [of resources]. But what you find there are colonial or post-colonial early years recordings. You see things like [mocking the publications] “dancers in an African village dance and they don’t get tired. They dance around the women as if they want to have sex. The women wiggle their waists and look at those males in a seductive way. This means these people only dance for sex.” laughter

Kwezi Tabaro: [laughs] It sounds like a National Geographic narration.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdanies: [laughing] …of the 1930s and 20s. And some 1940s and 50s. So, in all that you will realize that there is objectification of the African body. You look at it as an object. You look at it as a fetish that can be fetishized. So, the kind of scholarship that we are trying to introduce to our dances is that, no, our dances are not about that body.

There is a wonderful scholar in the US who wrote and book and they had the 3 Bs: Boobs, belly and bum. She is called [Brenda Dixon] Gottschild. She talks about how, even in the US, in the 60s they were looking at a black female dancer as someone who was just expressing the boobs, the bellies and the bums. So, there is a lot of objectification going on and what we are trying to say is that our knowledge in our dances and music goes beyond the body. That’s where I introduce this idea of multiple intelligences. When we do what we do, there are so many intelligences that we apply to the activities we do. It’s a science: there is kinesthetic intelligence, there is music intelligence, there is emotional intelligence, there is even mathematical intelligence if we are to go into an analysis of dance forms, you will be surprised that in some cases dance has been used to teach children how to improve their mathematics! We are trying to expand the thinking.

We are trying to de-objectify the histories and de-objectify people’s thinking about dance. That is Howard Gardner. So, I bring Howard Gardner, the theorist, into this conversation as well. That’s what my mission is. It is to try and show that our knowledge is varied and valuable knowledge that has the mind but also the body.

Kwezi Tabaro: I would like to follow up this interesting view with a very Ugandan example: we have had in the last 15 years victimization of the arts, and this is as broad as it gets, whether it is the performing arts, drama, dance or arts in general, by our policymakers and more especially politicians. The president in a recent national address extolled the greatness of Ugandan scientists: doctors, researchers, and engineers who had contributed greatly to the country’s effort to beat COVID-19, but also deal with the issue of the floating island on River Nile.

In the same breath he also admonished the artists who, he wondered, what else they have to contribute to Uganda and asked “what is the usefulness of studying Shakespeare?” So these are some of the conceptions that continue in most of the African countries, it’s not just the president, but I am sure you’ve heard it from many other African presidents who think that perhaps if Africa had more scientists than artists, maybe the continent would have progressed much further and much faster. From your approach, it’s something you disagree with because your conception of total education does not split between the arts and the sciences but actually emphasizes the role of the arts in teaching the sciences.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Yes, and I respectfully defer from the president and the people who belong to that kind of thinking. The president, not many years ago, was rapping and his song became very popular. Well, I don’t know whether he was wasting his time when he did that and I am not here to make political statements, to be very honest with you, but I just want to say that the Arts are so close to us and [especially] in this COVID-19, I will ask a question to all the listeners: during this lockdown, who hasn’t listened to a song? Who hasn’t read a poem? Who hasn’t watched a movie? I don’t know how many people have read verdicts of judges during this lockdown. I don’t know how many people have read reports of engineers during this lockdown. The Arts speak for themselves, so if there is someone out there who has been listening to the music, who has been watching movies during this lockdown, then that is the power of art, and then you will know how valuable the Arts are.

So, the Arts are central to how society manages issues, the arts are central to how societies express ideas, the Arts are central to how societies innovate. Tell me about a wedding without music and dance! Tell me any birth without music and dance! Tell me any achievement without music and dance!

I think what we haven’t done is to try and build institutions and structures that can support the Arts so that their value is evidenced and quantified. For as long as people don’t see that quantification, they will still think that the Arts are not valuable, but they are, only that it is very difficult to quantify their impact because the nature of the arts is that they emerge within communities, and it is very difficult, sometimes, to track and add value to what communities do; the people who listen to music in their houses, you cannot add value to that because they listen to music and appreciate it. The people who dance inside their houses, you cannot track that and add value to it but they do it. So, that lack of a system that codifies the value is what makes people think that the arts are not that important.

Look at Hollywood, it has moved mountains. Look at the artists who are donating, and I don’t want to put money ahead of art, but they are donating; Lady Gaga just had a concert where they raised more than [$35 million] that they donated to WHO for this COVID epidemic. Tell me any community that has raised [$35 million] during this epidemic and donated it to an organization like WHO. That is the power of the Arts.

But you also need to remember that there is always fear that people have for the Arts; the colonialists banned the Arts because to move your agenda you need to figure out how to deal with the arts [since] they are so powerful. The Apartheid regime banned artists. So, you also need to look at that angle; from what perspective is this person belittling the arts? Is it in the interest of the country or is it in their own interest? People need to ask those questions.

Kwezi Tabaro: Mabingo, there is a question coming in from Lillian Mbabazi; she is interested in knowing how you have integrated that experience in your dance pedagogical experiences with people who have additional needs such as the physically challenged or those with visual impairments. If so, what insights do you share from that experience within the notion of inclusivity?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: That’s a very good question, thank you, Lillian. It goes back to this idea that, for me, when we enter that space of sharing art, we don’t judge. Two, as we do it in our communities, everybody comes and they have a contribution to make: it can be a chant, it can be playing an instrument, and it can even be just their presence in that space that allows us to create structure. I think once we realize that, that participation takes different forms, then you identify how to activate those different forms of participation and once you activate them and individuals come and participate and create experiences, then that slowly creates a safe space for every individual in that space to feel included, to feel valued and to feel part of that experience.

Kwezi Tabaro: My very last question before we address all the other questions from the participants is on the performing arts: dance, drama as a cultural export. We live in very interesting times where countries like China are on the ascendency and we see that coming, not just with military and economic might like many of us will be familiar within Africa, but more increasingly, there are a number of Chinese cultural products that we are interfacing with; I know many people have watched that popular Chinese movie Wolf Warrior 2. Do you think China can give Africa a good lesson on how far cultural exports can go towards improving your diplomacy and influence in the world?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Yes, I have watched Wolf Warrior 2 and I have written an article on China and how it is transforming the traditional music and dance industry back in my country. I think that given the fact that we almost come from the same background like China; China was never colonized but it was occupied and humiliated—and now it has really been able to transform its society and create a middle class that is more than 500 million people in less than 40 years! That is unprecedented in human history! I think in that sense, we have some intersections within our historical realities with China. We have a number of things to learn from them and we always have to ask ourselves that question: how have they managed and what are some things that we can learn from them?

When it comes to how we interact with whoever is stronger than, depending on how you measure strength, Africa, for me it has always been that we need to have our interest; what are our interests? We bring our interests to the table and then you bring your interests. If we agree that you will meet some of our interests and we can meet some of your interests, it is a win-win. If we don’t agree, let it be a lose-lose. That’s how I have always seen things; I am now talking from a pure perspective of neo-liberalism. [Laughs]

So, I think in that sense we need to set the agenda. We need to set a vision for ourselves as a country but also as a continent, and then we need to see how we can mobilize people locally so that all of them buy into that decision and that dream, for the country but also for a dream that empowers individuals. And…

Kwezi Tabaro [Interjects] What is the role of scholars like yourself in advancing this vision and dream?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: I think the role of a scholar, one, is to be a public intellectual, not only an academic intellectual. I think within the continent, we are still lagging behind when it comes to public intellectualism. We hide in universities and we publish in journals that people can’t access in our own countries and we feel good about it. That is not enough. That’s not the 21st-century thinking. The 21st-century thinking is for that academic to go out and be a public intellectual; to mobilize the masses. So, I think we need to contribute towards the process of creating a critical mass locally and we have to be part of that process or even lead in some cases. So, for myself as a scholar, I see myself taking that role of mobilizing a critical mass and using that critical mass to push the agenda for dance, the agenda for the arts, and the agenda for our interests as a country and as a continent.

[…]

Kwezi Tabaro: In the spirit of going outside the ring-fence, when is your upcoming book being published and what efforts are you putting in place to see that this is not just a conversation between you and your fellow academics?

Dr. Mabingo Alfdanies: My book will be published on August 14, 2020. I am really stomping. This is my first book tour. You can call it virtual and I am going to be out there parroting and publicizing this work but also, just to tell you, that my book came from research that I did with 8 wonderful indigenous dance practitioners in Uganda and I let their voices speak for themselves in this book. It’s not a Mabingo book; that’s not how I see it. I see it as this knowledge and collaborative effort that has emerged from the wonderful work that these eight: Ronald Kibirige who works with communities of disadvantaged children in Uganda, Mariam Mugenyi of Afridance troupe, Watimoni Matthew of Watmon group, Ssenkubuge Mathias all the way from Rakai, Olivia Namyaalo who has worked with various communities in Uganda, Brian Magoba, Herbert Mukungu and Collin Lubega, a wonderful dancer, teacher, thinker who has worked with various communities in Uganda and abroad. These are the people that gave me the courage and the confidence see that our knowledge is variable and I am standing on the shoulders of these eight giants to tell the world that here we are, this is what we bring to you and this is how we want you to see us.

Kwezi Tabaro: Lastly, there is a question from Sylvia Nanyonga; “Thank you Dr. Mabingo for your very informative presentation. Can you share with us how you have negotiated the notions of authenticity in exporting dance culture from Africa to other cultures outside of Africa and to what extent is dance in these contexts African?”

That’s a very good question Sylvia and I know Mabingo will want to wrap it in academic language but I think there are two very relevant examples that many people will relate with, the [Triplets] ghetto kids in Eddy Kenzo’s music videos and also a group in Masaka that appeared in Drake’s recent song, “Toosie Slide”. So, there seems to be an incentive in the West or interest in things that the ordinary Ugandan would find quite ordinary, but they seem to arouse some interesting kind of interest on the global scene.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Yeah. I think that in terms of authenticity, it is an idea that is contested; there is a lot of debate about authenticity. One of the things that really makes this idea contested is “what is authentic?” because all traditions emerge at an intersection of various traditions and as society progresses, you get continuities; things that are retained and changes. I think it’s really tough, to be very honest with you, but I try, especially outside the contexts where these dances and music are performed, to emphasize the fact that I am adapting that material to a new context because you can’t recreate it and within that, I tell my students or my collaborators to pick ideas.

If I share with you this experience, what ideas do you pick instead of the material, because there is a difference between the idea behind the material and the material itself? The material may land you into appropriation but if you go for the idea and figure out how you can apply it, the phenomenon of that art keeps growing. In terms of the popularity of whatever you call Ugandan dances in global culture, I think there are nutrients we need to recognize; my work on this particular book focuses on some of those indigenous dance forms but I recognize that you have urban street dance forms that have emerged; you have afrobeat, you have spaces that you never had before, especially online platforms, that people are using to disseminate that knowledge.

So, as we think about our art, we need to think about the trends outside these Arts that are driving the way we create art, the way we disseminate art, and the way we share art. I think the value for our arts is high, and we need to strategically position ourselves so that we develop mechanisms to benefit Uganda, as communities from the art that we create and the art that we share. We also need to accept that this is going to evolve, we will keep innovating and come to terms with the fact that innovation will just continue. There are a lot of forces that are intersecting to create something that I think will be wonderful and if we seize the opportunity, and cultivate it, we stand high chances of benefiting as creatives, as an economy and as a society in Uganda and across the African continent.

[…]

Kwezi Tabaro: Thank you very much Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels, and we look forward to your upcoming book, “Ubuntu As Dance Pedagogy In Uganda”. It is an honor for the LéO Africa Institute and the LéO Africa Review to interview you on this virtual book tour. Hopefully we can interview you much later in the year when the book is finally out. I would like to thank you for your time and insight. I would like to thank our wonderful participants; you have made this conversation very enlightening. Thank you, ladies and gentlemen.

Dr. Mabingo Alfdaniels: Thank you Kwezi Tabaro for hosting me and thank you LéO Africa Institute for creating this platform.

Kwezi Tabaro: Thank you.

Editor’s note: The conversation has been slightly edited for easy reading and fact-checking.