Ethiopia and Egypt are on the brink of Africa’s first major climate change inspired regional conflict that could draw in 10 other riparian countries. What are the stakes?

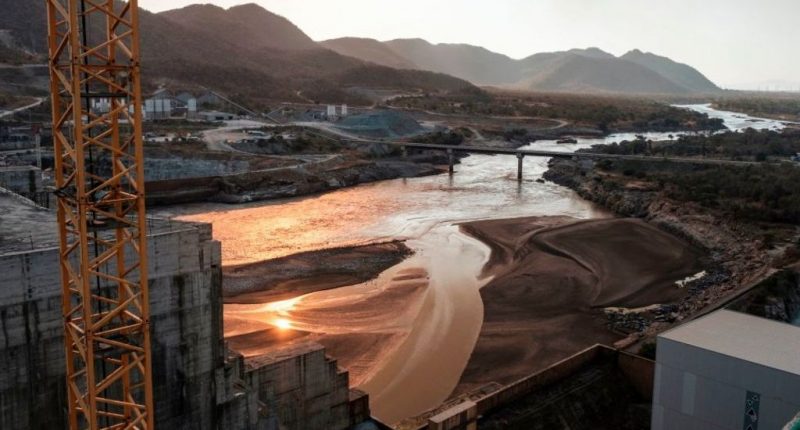

Those are the undercurrents around the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) – a facility designed to meet Ethiopia’s burgeoning energy needs with its estimated capacity to produce 6,000MW of electricity.

Built on the River Nile, the Ethiopian dam is the largest in Africa. Egypt however has been at loggerheads with this project since its construction kicked off nearly a decade ago arguing it is a threat to its national livelihood.

For Ethiopia, the dam is symbolic for a country of 110 million people, 70% of whom do not have access to electricity. The Horn of Africa nation has its eyes firmly set on becoming an industrial power on the continent.

“We do not in fact face any serious challenge of national unity. We have always been united as the contribution and stance of the Ethiopian people for the GERD demonstrates” Alemtsehay Meseret, the Ethiopian Ambassador to Uganda told the LéO Africa Review in an email. This was in response to a question about the significance of the dam at a time of domestic upheaval in Ethiopia.

“Even before the 2018 political reform, where many Ethiopians in the diaspora had some grievances against the government, they have contributed their share of support,” Meseret added. The consensus in Ethiopia is that political leaders have put aside their ideological differences in support of the dam.

“Egypt wants to maintain these outdated ‘historical’ privileges in the name of reaching an agreement on the filling and operation of the GERD.”

– Zerihun Abebe Yigzaw, Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs official

It could be argued that the completion of the GERD will open the floodgates for major irrigation and hydropower projects in upstream countries. Uganda, one of the upstream countries, is in the final lap with its 600MW Karuma hydropower project built over the River Nile in mid-northern Uganda.

National leaders in the other upstream countries in East Africa, which is in the throes of an infrastructure binge, are watching keenly the developments in Ethiopia.

The stakes of this infrastructural behemoth were raised when various media reported in mid-July that Ethiopia had started filling the dam’s reservoir. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed seems to have made the completion of the GERD a legacy-defining project. The gripe of the Egyptians is that the dam threatens to cut off the Blue Nile—the Ethiopian branch of the Nile which constitutes 85% of the river’s waters and is Egypt’s exclusive source of freshwater for irrigation.

The two countries keep exchanging threats and terse statements in a battle that will intensify as filling of the dam goes on. Diplomatic efforts to iron out an agreement have not gone smoothly.

Egyptian President Fattah El Sisi and Ethiopia’s Ahmed Abiy have been huddled in negotiations within their respective governments for years. Outside, the parties have courted the mediation of the White House but it all came to naught—matters not helped by the short attention span of President Donald Trump.

One would wonder, why does this dam mean so much for Ethiopia? The GERD is said to have created 12,000 jobs since works on it commenced. Constructed at a staggering $4.7bn, the GERD project has seen the resettlement of over 20,000 people.

The dam was conceived as a statement about Ethiopia’s vision for and commitment to its self-sustenance and development. The project is managed by the state-owned Ethiopian Electric Power and is financed by bonds purchased by Ethiopians at home and abroad. No international financier was involved from the onset of the project that has been hailed as an engineering feat.

The Gilgel Gibe III on Omo River was previously Ethiopia’s largest dam with a 1870MW capacity but it has largely been used for flood maintenance and its power generation capacity for the fast-growing nation has been deemed insufficient.

In the early 2000s, Ethiopia started a series of dam construction projects under the Gilgel Gibe franchise; I, II, and III but it has since channeled its energies toward the GERD after the other projects suffered delays and technical hiccups.

Under Ethiopia’s current Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP), the country had a target to increase electricity generation capacity to 17,000MW by 2020. At the start of the 2010s, the GERD became the vehicle of the GTP and the embodiment of the country’s vision.

According to some analysts, Ethiopia could become a regional hydroelectric power player. Transmission power lines crisscrossing Sudan, Djibouti, Kenya and connecting with Ethiopia could lower the cost of power and make it more available for rural communities in these countries.

Sustainability issues

Richard Bazira, the Executive Director of Water Governance Institute (WGI), a non-profit based in Kampala that is concerned with policy and governance of water resources says the sticking issue for the dam construction was sustainability of environments around the Blue Nile.

He says a 2013 inspection panel report to which WGI contributed raised concerns on the ecology of the dam site and the people who were being displaced. Environmentalists have also pointed out that Ethiopia’s highlands and mountainous terrain in general are susceptible to erosion. They say this could cause sedimentation of the dam reservoir in addition to the recurrence of landslides. Fish farmers around the Blue Nile have also complained about dwindling fish stocks.

The panel constituted members of the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

On the politics of the GERD project, Bazira says Egypt and Sudan may have to take a back seat because they are stuck in a time warp. “Egypt and Sudan have been reluctant about new agreements because old agreements favour them. Ethiopia and Uganda may have been part of those agreements but they were not signed by Africans,” he says.

“Egypt is in some kind of war with upstream countries but there is not much they can do,” Bazira adds. He stresses that for a long time countries like Uganda and Ethiopia have been excluded by these old agreements and it is perhaps natural that events are taking the current course.

Egypt is part of the Nile Basin Initiative that comprises ten other states; Uganda, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Burundi, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, and DR Congo. Eritrea participates as an observer. The Initiative was established in 1999 to build cooperation between members on the use of the Nile Basin shared water resources but it has been dominated by sabotage and backpedaling.

In 2017, Egyptian President Sisi went on a week-long tour of African countries. Two of those; Rwanda and Tanzania, are members of the Nile Basin Initiative—observers interpreted this as a charm offensive after years of Egyptian bullying tactics. It was a stark contrast to the time when the 1929 and 1959 colonial agreements held sway on all matters River Nile.

In June of that same year, Sisi attended the first-ever Nile Basin summit in Kampala. He thanked the host, President Yoweri Museveni for the “historic” summit and added, “The River Nile unites us and does not separate us.” Then Ethiopian Prime Minister Mariam Desalegn was also in attendance.

Away from the smiles and cheer, no deal on the Nile was struck, however.

AU attempts

Attempts by the African Union (AU) to mediate matters have hit a dead end after a virtual extraordinary meeting called by AU chairman and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa did not make much headway.

Analysts have said the AU should have taken a lead from the get-go since tensions built up over the last ten years. At the start of the dam construction in 2011, Ethiopia got the perfect opportunity to go ahead with the mega project after a wave of protests swept over Cairo, the Egyptian capital, in the famous Arab Spring.

Fast forward to 2020, and similar events are in high gear in another capital, Addis Ababa, also home to the AU.

“It is more than 73% complete. And we are expediting the electromechanical and related works,” says Zerihun Abebe Yigzaw, an official at the Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Member of the Ethiopian Negotiating Team on the GERD.

Yigzaw states that “Egypt wants to maintain these outdated ‘historical’ privileges in the name of reaching an agreement on the filling and operation of the GERD.” He argues that many of the technical differences regarding the initial filling, operation of the dam and dispute resolution mechanisms involve Egypt’s long-term interest to keep its veto power over the waters of the Nile.

In all talks, Egypt has insisted on a binding agreement that stipulates that the filling of the dam will not affect the flow of water to its side. Ethiopia has flatly rejected this.

For future rights on the use of the River Nile, the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA) formulated in 2010 in Entebbe, Uganda is on course as the definitive guide on how the Nile waters can be shared. Last year, Uganda signaled its intention to ratify the agreement joining Rwanda, Tanzania and Ethiopia.

According to various reports, the groundbreaking agreement requires six countries to ratify it for it to come into effect. This means the above four countries would need two more members of the Nile Basin Initiative such as Burundi, or South Sudan to get on board for the CFA to be a legally binding instrument. This would leave Egypt and Sudan, who have shunned the CFA, in a bind.

Article 15 of the CFA creates a permanent institution called the Nile Basin Commission. It will be the basin-wide authority with a clear mandate to approve national water resources, investment plans and programs for Nile Basin states.

The office of the Egyptian High Commission in Uganda could not be reached for comment.

Timeline

- 2 April 2011 – Then Prime Minister Meles Zenawi lays foundation stone for the dam’s construction

- 15 July 2012 – Then Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi visits Ethiopia for talks over the Nile

- 28 May 2013 – Ethiopia diverts Nile waters to begin construction of dam wall

- 23 March 2015 – Agreement is signed between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia called the Declaration of Principles

- 20 January 2018 – Ethiopia rejects Egypt’s proposal to involve the World Bank as a technical party in negotiations

- 15 July 2020 – Ethiopia starts filling the dam reservoir