To a very great extent, everyone in society feels alienated from society at one point in their lives. Possibly that is why the greatest heroes of the cinema age have been loners who happen to be underdogs due to this alienation.

These heroes shape the arc of life’s peculiar circling when art imitates life and life imitates it back.

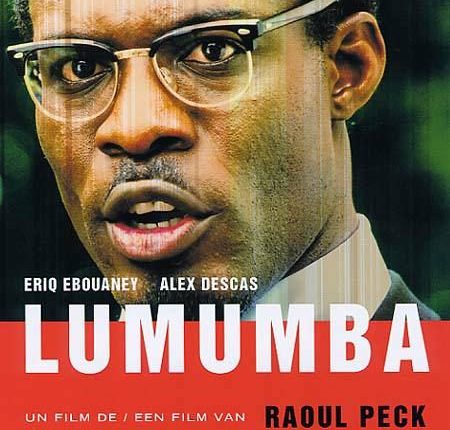

For instance, you’ll have a character like Patrice Lumumba in the 2001 eponymous biopic about how the United States conspired to bring about the death of the Congo’s first democratically elected prime minister and replace him with “Brutus” Joseph Mobutu. The latter a bloodthirsty, money-grubbing tyrant.

Raoul Peck’s film (a feature, not a documentary) starts from beyond the end with Lumumba’s assassinated body being exhumed by Belgian soldiers so it can be cut up into smaller pieces and burned in oil drums.

In real life, “Stinky” (the CIA’s nickname for Lumumba) was so feared by the imperialists that Mobutu had Lumumba’s body disinterred from its shallow grave in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi) and flown to Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) where it was then dissolved in acid.

As the story in the movie continues, Lumumba’s voice (or actor Eriq Ebouaney’s narration, if you want to get technical) recalls his early days as a beer salesman, a trade that helped turn him into an orator.

“He had this tremendous ability to stir up a crowd or a group. And if he could have gotten out (of prison) and started to talk to a battalion of the Congolese Army, he probably would have had them in the palm of his hand in five minutes,” US diplomat Clarence Douglas Dillon would later say.

In the film, the beer Lumumba promotes has a rival owned by Joseph Kasavubu—who later becomes president while Lumumba is named prime minister. It is Kasavubu who eventually orders the arrest that leads to Lumumba’s murder.

Before that, Lumumba becomes a leader of the Congolese National Movement. He later becomes prime minister and his attempts to end the Katanga secession, a mineral-rich province in Congo, gets him tagged as a communist. He is then “liquidated” by the CIA in cahoots with the odious Mobutu.

Lumumba, in the movie, is an amalgam of several aesthetics and orthodoxies.

On one level, his physical death was a triumph of the metaphysical power that mankind wields to beat the odds.

As Jean-Paul Sartre wrote: “Lumumba alive and a captive is a symbol of the shame and rage of an entire continent . . . Once dead, Lumumba ceases to be an individual and becomes all of Africa, with its will toward unity, its dissensions, its discord, its strength, and its impotence.”

Most importantly, though, was the fact that Lumumba was once a nonentity seemingly condemned to the nothingness that consumes the very core of our existence.

Therein lay his appeal: his gladiatorial battle against long odds in a short life.

To be sure, a life the philosopher Thomas Hobbes described as solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Lumumba encapsulates this tragic side of life, yet he also incarnates the triumph of the human spirit with his fighting spirit. And this taps into our unconscious need to rage against the dying of a light, if you will.

The dying of a light enkindled in the poetry of Dylan Thomas and in Joseph Conrad’s Marlow in Heart of Darkness, who described Belgium’s Congo as an “accursed inheritance to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and excessive toil.”

The fact that Lumumba seems to be a loner who is underrated by the Belgian colonials makes him anti-colonialism in the sense that he plays by his own rules. Furthermore, his dreams and aspirations are not circumscribed or hemmed in by their view of Africans.

Aimé Césaire, the Martiniquais poet and apostle of négritude, wrote that for all of Lumumba’s flaws, one would remember “his prodigious vitality, his extraordinary faith, his love for his people, his courage and his patriotism . . . one may not approve of all the political acts of Patrice Lumumba. No doubt he made mistakes . . . [but] at least his heart never flinched.”

This alone gives his character a powerful appeal.

All told, a lot of societal mores, values or belief systems (what Marx called the superstructure) are shackles that leave us ‘free but everywhere in chains’.

So when a person like Lumumba breaks the mould by merely being himself, we are inspired.

Indeed, we are all essentially rebels or wannabe rebels. If you look around, you will notice that it is fashionable for people to claim to be ‘crazy’ and eccentric. That’s because this marks them out as iconoclastic, rebellious and best of all, as individuals.

Yet, it must be said, most people’s craziness is a mere affectation; a posture and not a reality. Most of us are conformist and are as conventional as yesterday’s news.

We are unfree, and we know it. That’s why persons like Lumumba who exemplify breakout notions of nonconformity and individuality (at the risk of being social lepers) appeal to us.

Just look at all the iconic real-life and movie characters and you shall notice one enduring motif: they were themselves in spite of themselves.

This singularity of self is of a heroic emotion that all of us wish we had. But we fear to be cast out by society because we are different.

Therefore, we would rather live vicariously as anti-establishmentarians through the movie characters of those outsiders who, like Lumumba in this film, expand our possibilities.

That way, we don’t have to shine as bright as the stars do. Since we fear, our lives might be abbreviated to the length of a movie. As Lumumba’s was.

For, Lao Tzu said, ‘The flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long.’ So it was for Patrice Lumumba.