The old warriors for the African cause today are more likely to die of, well old age, surrounded by their large family and their vast estates than to be slaughtered in their prime. This is a cause for celebration. Africa is more stable today than 60 year’s ago. As the pot-bellied former revolutionaries of the most recent age of heroes retire their speeches and stories having lived long enough to face not the dark plots of faraway superpowers but rather the ordinary ailments of high blood pressure, diabetes and gout, the younger generation pauses to ask if heroism is now history.

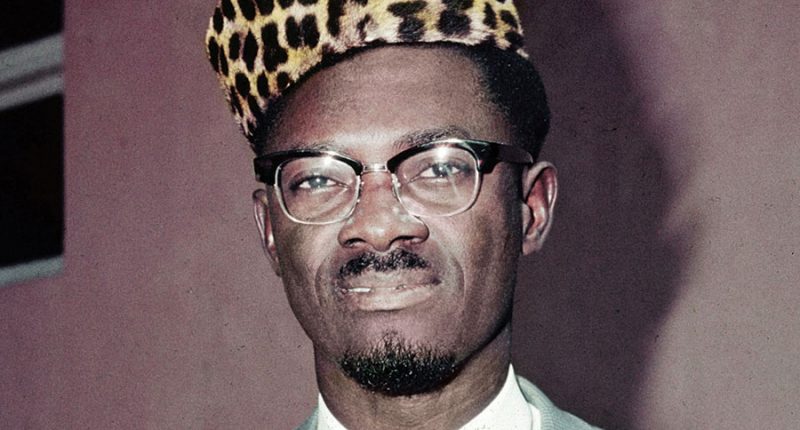

It has been six decades since Patrice Lumumba died – shot like a dog and discarded. That Patrice Lumumba is a Congolese hero, an African one too is of no doubt. However, whether he is or would be a hero for our times is debatable. This is not his fault. His name will be forever celebrated. Gen Idi Amin Dada named one of his sons Lumumba as did my friend Tony Otoa, the politically conscious corporate dealmaker with an eye to the new dawn of “Africa rising”. Lumumba’s bravery and vision, for a strong, united and independent Congo, one that would take its place in the assembly of free and self-governing African states, was a struggle which ended his life. So perhaps an African martyr is a more befitting honour. Martyrs rise beyond their times to speak across generations.

What we know, additionally from the death of Lumumba is the price that Africa had to pay for it. It seems too great a price that the death of a single individual would reverberate so. But it did. The death of a committed nationalist like Lumumba at a time when the struggle for unity places a nation at crossroads is extremely disruptive. This lesson is fresh in our memory with the more recent death of Comrade John Garang De Mabior. Both men died at the hands of violent imperialism. The assassination of committed leaders yesterday or today can undo the critical work of nation building and force survivors into the kind of confusion to which we now turn.

The stability revolutionaries still alive may have gained the running of a government for their “heroic” efforts at liberation wars or coups but lost in a clear vision of a free, united, confident Africa. The old warriors still holding out for hope that their struggles have not been in vain – only have to face the fact that there are in fact no new heroes.

Take your run-of-the-mill African big man today, any of the many suits with large entourages and even bigger speeches that have filled the shoes of Mobutu Sese Seko, Robert Mugabe or General Ibrahim Babangida. Like the late Muammar Gaddafi, another victim of violent imperialism, they would argue that their state’s sovereignty is part of the edifice of genuine African liberation because it is a vanguard against resurgent colonialism. Their people need them to safeguard the gains of the revolution is often repeated. Their vision of their countries is suspended in time and state rituals do the job of keeping off of history’s revolving doors any new efforts to redefine the near future. They carry this protective reasoning to how they characterize their opponents. The men and women involved in the political process, if opposed to them will be painted as unwelcome meddlers with the work of history. The unlucky ones are shot and discarded like dogs or given treatment far worse than Lumumba received at the hands of his American controlled captors. That is because just like liberation yesterday and the fight against imperialism their opponents must always be traitors and quislings acting for external enemies.

This stopping the clock of progress at the fingers that point externally has a dubious effect. This is because nationalists claim they continue to stand against imperialism and its agenda to ward off criticism but when for example, they are judged on their governance, they answer that they should not be held to a standard of Western governments – many of whom were colonial powers or benefited from the colonial enterprise. For the most Mobutuist, the daily contradictions of fighting imperialism while living up to the standards of former imperialists fills the national papers with such hypocrisy that one cannot tell when neo-colonialism starts and ends. The first is of course that nationalists require European markets, American arms, Russian advisors and Chinese technology to fight imperialism.

One area is clear in the dubious doublespeak on “democracy”. It often is accompanied by the repeated fallacy of “African solutions to African problems” which is a euphemism for the “leave us alone” neo-nationalists. The argument is split in two – between rulers and the governed. On the one hand the rulers will cast themselves as resisters of imperialism when they are in government. At the same time, when they hold an election, packed as these are with violence and irregularity, they argue that no “European” standards of democracy should apply. The European in question is asked to recognize this as an African process. The question as to the quality of the vote, a system now accepted as paid across Africa is one in which voters have little say. It is as if this system of enacting choice, the essential ingredient of freedom is not the province of the governed. African “voters” rarely get to keep the question of what the democracy is as a subject for their own determination, away from Europeans, their own leaders, or even aliens.

It follows therefore that today’s hero would need to be a one of commonsense. He or she would have to successfully argue that freedom for the African is not concomitant with being “left alone”. That even in a room where history is absent, where imperialism has been exorcized, where race, communism, capitalism, socialism or voodooism is expunged, freedom can be victim to more common fare aspects of irresponsible and unaccountable rule.

He or she would need to point out that the inertia in which today’s nationalists wallow; where heroism is recursive and cannot be reproduced beyond the independence era or the one that followed (in which independence failed and required liberation to set it right) is a barren Africa.

It is a zombie world Africa that can produce no new heroes. The time loop in which the heirs of the liberation struggle are only required to enact as ritual the heroism of the past as they retire those who are lucky to be alive with ribbons and honours saps the energy of the most gifted of the new generation. It is bad enough that entire sections of the government and politics are devoted to endless praise that is deployed to guard the “fruits of the liberation”.

Zombie o, zombie (Zombie o, zombie)

Zombie o, zombie (Zombie o, zombie)Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go (Zombie)

Zombie no go stop, unless you tell am to stop (Zombie)

Zombie no go turn, unless you tell am to turn (Zombie)

Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think (Zombie)Lyrics to Fela Kuti’s “Zombie” (1976)

Finally, anyone named Lumumba today must add that in the airlessness of the permanent legacy of only one set of heroes, the contributions of the contemporary “democratic hero” who emerges from the battlefield of an election is likely to be squandered.

Why are ballot heroes so different from Lumumba?

Is Mwai Kibaki not cut from the same cloth as Lumumba or Etienne Tshisekedi? Is Lazarus Chakwera a second-rate hero? Could it be that the problem with the ballot heroes is the association of democracy with the West, and by this with imperialists of old? Is this the reason that conversations about democracy suggest that Africa should be ‘left alone’ to find its own grounding in this form of government? Is it defensible that freedoms and rights under “African” democracies should be distinct from similar freedoms in other “democratic” parts of the world?

Today’s hero would need to address these questions and commit, in my estimation considerable effort to build a movement for self-government resolving these matters so that perhaps the new nationalism that emerges focuses on building better societies not just victorious political parties. It would be a rejection on the present impasse that self-government, no matter its mistakes, should produce no new heroes.

Angelo Izama is a Ugandan writer, analyst and Head of Faculty at the LéO Africa Institute.